Book review - A State in Denial, by Margaret Urwin

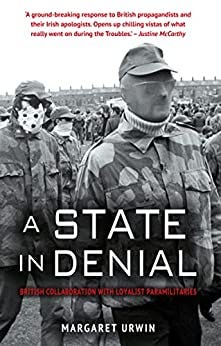

Margaret Urwin, A State in Denial: British Collaboration with Loyalist Paramilitaries, (Mercier Press, 2016).

A State in Denial is the second of two major books on the Northern Ireland Troubles to emerge from research by the Pat Finucane Centre and Justice for the Forgotten, each making extensive use of official documents from the National Archives.

In the previous work, Lethal Allies, Anne Cadwallader of the Pat Finucane Centre presented the evidence that proved beyond doubt the existence of a loyalist gang involving members of the RUC and Ulster Defence Regiment responsible for some 120 killings in Mid-Ulster in the 1970s.

Cadwallader demonstrated that opportunities to investigate the gang's activities were repeatedly passed up, and paramilitary infiltration of the security forces went unopposed despite official knowledge that this was the main source of loyalist arms.

While the existence of the Glennane Gang is now generally conceded, some critics of Cadwallader's book still resisted her conclusions about the role of high-level collusion in allowing the gang to operate.

A State in Denial, by Margaret Urwin of Justice for the Forgotten, leaves the holdouts for the bad apple theory with an even more difficult task on their hands. She turns the spotlight firmly on the policymakers, and evidence of high-level collusion emerges on almost every page, from MI6 officers recommending collaboration with loyalist 'vigilantes' in the early 1970s to the Chief Constable lobbying on behalf of the Ulster Defence Association in the early 1980s.

A key turning point came with the introduction of internment early in the conflict, which was applied solely to republicans. While IRA members could be detained solely on the basis of intelligence, loyalists could only be arrested for the purpose of criminal charges. To defend this double-standard, the Government argued publicly that loyalist violence was not orchestrated like that of republicans. This line was maintained with a tenacity that had profound consequences. On a number of occasions loyalist violence was attributed to republicans, and evidence of the true perpetrators was suppressed.

The most notorious instance of this was the McGurk's Bar bombing, which killed 15 people in December 1971. Had its true UVF provenance become public, the authorities would have been under pressure to intern loyalists. Instead, it was portrayed by the authorities as an own goal by IRA members supposedly assembling a bomb in the pub. This was maintained even at the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) when the British authorities defended the so-called 'Irish state case' in which the Irish government challenged a number of abuses including the differential application of internment. The ECHR's conclusions, published in 1976, accepted the British account of McGurks and thus of the level of loyalist activity. The first official acknowledgement of the truth did not come until a report to the McGurks families from the Historical Inquiries Team in the 21st Century.

McGurks was only one instance of a more general phenomenon which shaped the whole British approach to the Troubles. The determination to avoid a confrontation with loyalists on the one hand, and to be seen as upholding the rule of law in the other, led to a policy of denying reality which further alienated nationalists and deepened political polarisation. A similar case was British unwillingness to acknowledge the UVF role in the Dublin-Monaghan bombings of 1974, at a time when officials were regularly meeting UVF leaders as a preliminary to its legalisation less than a week after the attacks.

Urwin argues that the indulgence of loyalist violence contributed to the breakdown of two major opportunities for peace: the power-sharing executive of 1974 and the IRA ceasefire of 1975. Yet the ultimate example of the policy of duplicity lasted almost throughout the Troubles. This was the decision to allow the largest loyalist paramilitary group, the Ulster Defence Association, to remain legal from its formation in 1971 until 1992. This was made possible by attributing attacks to rogue individuals or to a supposedly separate organisation, the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF). Yet, as Urwin shows, in internal government documents throughout the whole period, officials acknowledged that this was a fiction, the UFF was a mere cover name for a UDA whose leadership was up to its neck in sectarian assassinations. They nevertheless regarded attempts to make them acknowledge these facts in public with some irritation.

The bizarre nature of the situation was highlighted by American reporter Michael Daly, after a telephone conversation with the press officer at UDA headquarters, Sam Duddy, who openly avowed UDA assassinations. Daly described the UDA as 'the only terrorist organisation in Europe listed in the telephone book.' This policy was seen at its most ignominious in 1981, when UDA leaders were caught red-handed in their headquarters with a cache of submachineguns and ammunition. Other raids netted UDA intelligence files. Only one person, UDA leader Andy Tyrie, was eventually brought to trial in 1986. He was acquitted after an hour, and the UDA remained legal. Particularly disturbing was the role of RUC Chief Constable Sir John Hermon, who told the Northern Ireland Office in early 1982 that he had channels to the UDA other than his own Special Branch. He warned that in the absence of a political initiative that would placate the loyalists, there was likely to be a wave of attacks that the RUC could not prevent.

While concentrating on official documents from the 1970s and 1980s, Urwin does note later revelations from successive investigations into the murder of Pat Finucane. The activities of informer Brian Nelson suggest that if anything, the actions of the state led to an escalation of UDA violence in the 1980s. Urwin analyses dispassionately the notion that Britain's partiality towards loyalist paramilitarism might have been justified by some higher reason of state. However, she concludes that the failure to protect citizens from loyalist violence deepened the conflict, and that it could have been confronted.

The one-sided security policy pursued by the British government had implications far beyond Northern Ireland, which also give a global significance to A state in denial. In the 1970s, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that the so-called five techniques' used on selected internees; wall-standing, hooding, subjection to noise, deprivation of sleep, and deprivation of food and drink, were ill-treatment but not outright torture. That ruling was, in effect, treated as a blueprint by governments around the world, inspiring the use of the same techniques in the occupation of Iraq and the war on terror.

It was, however, a ruling based on a lie. In 2014, the Pat Finucane Centre found internal documents in which British ministers admitted that the treatment of the detainees amounted to torture. That evidence is contributing to a new case at the ECHR which may yet overturn the precedent that has so often been abused. When that case comes, the evidence in this book will make it impossible to argue that British security policies were even-handed. Having marshalled so much official material, Margaret Urwin has shown us the wood amongst the trees. The legality of the UDA over more than 20 years was itself high-level collusion in its purest possible form, and this book is definitive documentation of it.

This review was originally published at Spinwatch on 19 December 2016.