Both sides against the middle: How to take down a peace process

Welcome! I’m Tom Griffin and this is my intelligence history newsletter. Feel free to share this article with the button below. This one is a little more personal than usual, partly by way of an introduction to the new readers who have arrived from Michael Sellers’ Deeper Look.

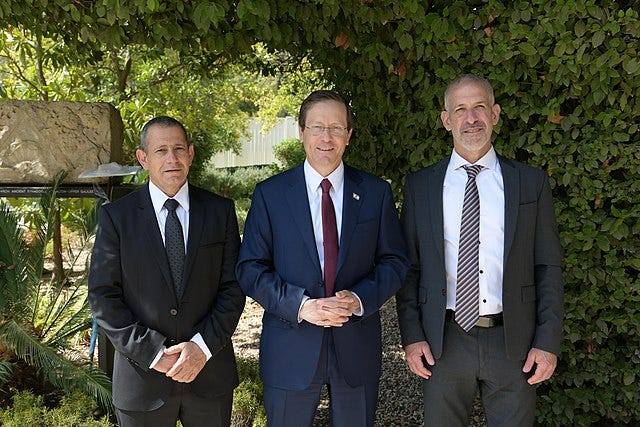

Former Shin Bet chief Nadav Argaman (left) with Israeli President Isaac Herzog (centre) and current chief Ronen Bar in 2021 (Amos Ben Gershom/Government Press Office of Israel, CC3.0).

Last week I wrote on the fallout from October 7 in the Israeli intelligence community. Since then, the recriminations have only escalated. The former chief of Israel’s Shin Bet security agency, Nadav Argaman, hinted in an interview on Thursday that he has incriminating information on Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. The current chief, Ronen Bar distanced himself from the remarks in a letter to Shin Bet retirees, writing that ‘a state body and its head do not use their power for purposes other than fulfilling their mission.’

Even without Argaman’s insinuations, there is plenty of evidence that Netanyahu Government had been prepared to turn a blind eye to Hamas funding if it helped undermine the Palestinian Authority.

This kind of dynamic, in which hardline opponents tacitly collude to undermine moderates, is one of the things which helped provoke my interest in intelligence history a quarter of a century ago.

My first job in journalism was at the Irish World, a newspaper serving the Irish community in Britain. I joined about a year after the Good Friday Agreement. It was a peak of optimism when the Irish peace process was held up as a model for other conflicts around the world.

That changed abruptly after 11 September 2001. I watched in consternation as the same Blair Government which championed the peace process embraced the War on Terror and the War on Iraq. The apparent contradiction concealed a deeper consistency. Peace in Ireland had been bolstered by British determination to stay close to US President Bill Clinton, and Blair was equally determined to stay close to President George W. Bush. (The same imperative remains at work even under President Trump. Blair’s key point man on Ireland, the former Washington diplomat Jonathan Powell, was at the centre of this week’s ceasefire proposal for Ukraine).

Although the Blair Government remained committed to the peace process, the new environment provided opportunities for its critics.

Anti-agreement unionists initially regarded the peace deal as a simple sell-out to the IRA. Naturally, anti-agreement republicans took the opposite view, that it was an IRA surrender. Yet an odd synthesis between the two positions began to emerge.

Hardline republicans argued that the peace process was the product of state infiltration, something to which the IRA had traditionally responded with ruthless executions. Hardline unionists increasingly agreed, blaming the politicians for snatching defeat from the jaws of victory. Crucially, it was hardliners in the Northern Ireland security establishment who were in a position to feed the narrative.

A number of informers were exposed during the 2000s. One of them, Denis Donaldson was murdered in 2006. A 2022 report by the police ombudsman rejected claims that police had leaked details of his whereabouts. The killing nevertheless showed how the anti-agreement narrative could fuel tacit collusion between opposite extremes to destabilise the peace process. A Sinn Fein activist was dead and unionist politicians blamed the mainstream IRA for the killing, although it was later claimed by anti-agreement republicans.

In the late 2000s, I began working at the UK National Archives for the Pat Finucane Centre. I gradually realised that I was in a position to shed light on the claim that MI5 had used long-run agent-penetration to promote the advocates of political dialogue within the republican movement. I was eventually able to identify all of the key intelligence officials in Belfast during the Troubles, the Directors and Co-ordinators of Intelligence at the Northern Ireland Office. With remarkably consistency, I found that from the late 1970s through the 1980s they had been wary of Sinn Fein’s political growth and had advocated measures to restrict it. It was only with John Deverell in 1990 that MI5 involved itself in back-channel diplomacy.

I put forward an early version of this argument in a 2012 openDemocracy article on the ‘conspiracy theory of the peace process.’ More formidable scholars have since reached similar conclusions on the basis of much broader evidence.

In the end, the Irish peace process proved too deep-rooted to be undone by a conspiracy theory, even one that retains a certain currency. The critics were more influential, perhaps, in deprecating the Irish model for other conflicts.

In a 2004 article for the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, The Spectator’s Dean Godson wrote:

The British fear that if the Sinn Fein politicos are undermined, "mainstream" Republican gunmen will bolt to the dissident Real IRA. This is similar to the line of reasoning that unless concessions are made to Arafat, Palestinians will move over to Hamas.

He went on to note that ‘Many British officials see Hamas and Likud as mutually reinforcing "hardliners."'

Two decades on, it seems that the British are not alone in that conclusion.