Jay Lovestone and the British

How MI6 observed an American Communist leader's ideological journey

Jay Lovestone with ILGWU leader David Dubinsky in the 1930s (Wikipedia, CC 3.0)

The repentant communist was a stock character of the Cold War almost from its beginning. Few such figures made a more remarkable transition than Jay Lovestone, who after heading the American Communist Party in the 1920s, became a key CIA agent in the international Labour movement in the 1950s.

Lovestone's biographer, Ted Morgan, called him a Zelig like figure (ref 1, p.ix). He was personally acquainted with world leaders from Joseph Stalin to Richard Nixon.

Intelligence was central to Lovestone's story long before the CIA existed. In the 30s he maintained links with certain Soviet agents even after his faction - the Lovestoneites - had been expelled from the Communist Party, a fact which coloured the FBI's view of him for many years (ref 1, p102).

The circumstances of Lovestone's journey away from communism in this period were murky even to the Communists themselves. In 1938 they burgled his apartment and reported to the Comintern evidence of his links to a suspected agent of the OGPU, the precursor of the KGB (ref 1, p.129).

Along with the FBI and the OGPU there was a third player in this tangled web, and its impact on Lovestone's career is perhaps the most mysterious.

Lovestone's comment that 'the British Intelligence Service was the only thing he had ever been afraid of', was recorded, somewhat ironically, in an 1935 MI6 report (ref 2, p.252). his connections with communists and socialists in Britain and the Empire, particularly, India, made him of some interest to the British. The official history of MI6 records that, while their lack of intelligence on the official Communist Party USA prompted complaints from sister service MI5, Lovestone's network was comprehensively penetrated (ref 2, p.252).

MI6 records remain closed to non-official historians, but some of the service's reporting on Lovestone has made its way into the National Archives via MI5 files which also include some interesting commentary on his activities in Europe, supporting anti-fascist refugees, particularly those aligned with the International Right Opposition, the Communist faction of which the Lovestoneites formed the American wing (ref 3).

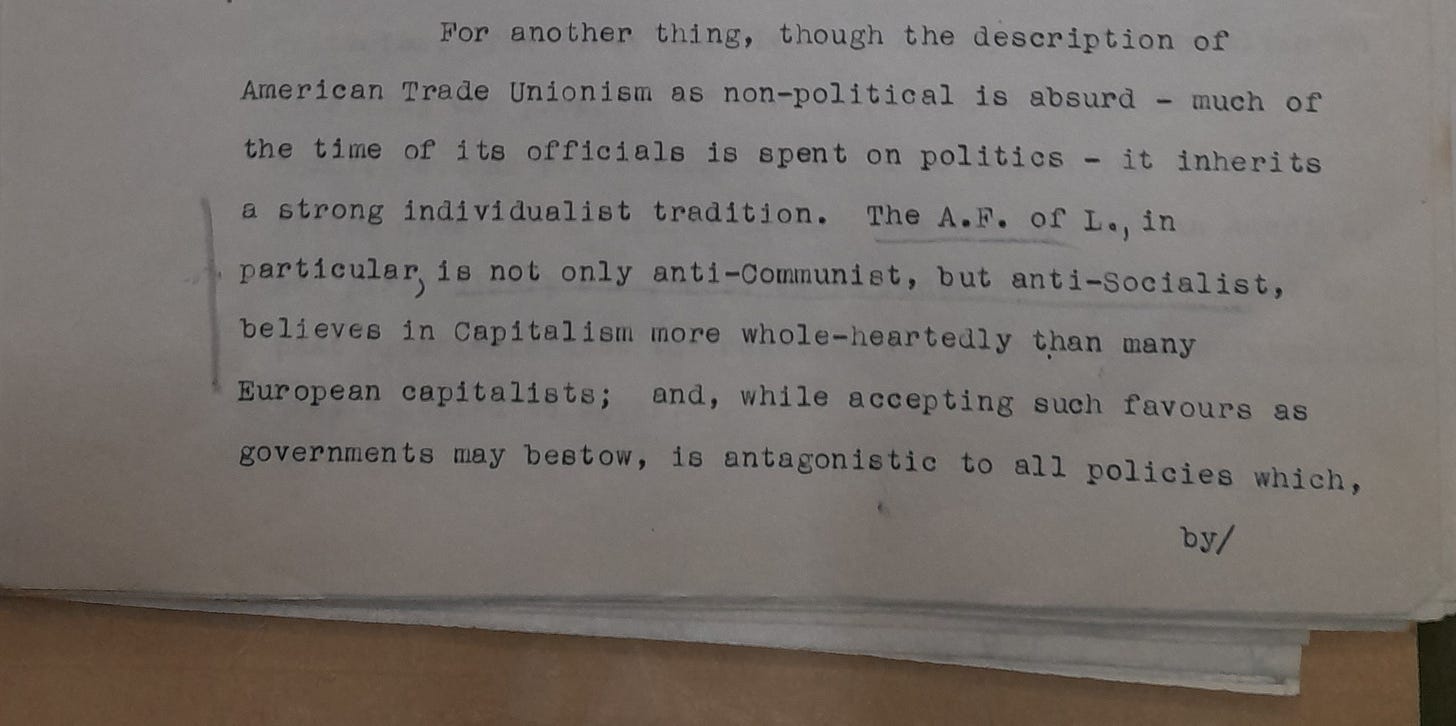

Extract from MI5 file KV2/580.

The British penetration of the Lovestone movement is particularly intriguing because of the confluence of interests that would emerge between the players in the late 1930s. The Moscow Show Trials made it abundantly clear that Lovestone had no way back into the official Communist movement. He became a close ally of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), the most staunchly anti-communist of America's union federations.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, Lovestone and the AFL were increasingly in alignment the British, primarily because of their continuing anti-fascist activities in Europe, but also because the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact gave support for the allies an anti-communist dimension. Lovestone himself would become labour director of the Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies, the main pro-Allied lobby group (ref 1, p.137).

One does not need to posit a covert dimension to explain any of this, but the covert dimension was there. Prior to American entry into the war, much of the interventionist campaign was under the influence of British Security Co-ordination (BSC), the organisation which ran Britain's secret intelligence operations in North America from the Rockefeller building in New York.

In 1941, British intelligence officer Sydney Morrell compiled a list of seven interventionist organisations under BSC control (ref 4, pp.23-24). According to Morrell, British influence was 'maintained through a permanent official in each organisation, who in turn, is in touch with a cut-out - and nerver with us direct' (ref 5). Two of the seven organisations concerned were AFL subsidiaries, the American Labour Committee to Aid British Labour (ALCABL) and the League for Human Rights (ref 5).

List of BSC fronts from FO 898/103.

Thomas Mahl suggests, plausibly, that the ALCABL official in contact with British intelligence was AFL vice-president Matthew Woll (ref 4, p.32). Nevertheless, its worth considering whether the British penetration of the Lovestoneites facilitated their influence over the AFL.

While the Lovestoneite organisation dissolved in 1940, many of its members shared Lovestone's subsequent political trajectory (ref 8, p.133). One former Lovestoneite in the interventionist movement was Francis Henson, the assistant to Sandy Griffith, an agent of the Special Operations Executive who was closedly involved in running the BSC fronts (ref 4, p.195).

In the 1930s, Henson had been one of Lovestone's lieutenants in a struggle with the Communists for the United Auto Workers (ref 1, p.125). Might he have been one of those passing information to the British at that earlier stage? It would provide one explanation for the quality of MI6's information.

What is established is that BSC was influential in lobbying for the creation of the Office of Strategic Services, and thereby shaping its successor, the Central Intelligence Agency. The labour operations of the BSC might therefore be considered a significant precedent for those of the American agencies.

If the AFL's intelligence connections would endure, its relationship with the British proved more transient. Following Soviet entry into the war the AFL and the British Trade Union Congress (TUC) fought 'a largely unseen war behind the war' over relations with the Soviet trade unions (ref 6, p.245).

One British view of the AFL at this time was documented in a report for the Washington Embassy by the distinguished socialist R.H. Tawney, who lamented 'a type of "business trade unionism" which has its place in labour movements but which is mischevious when exaggerated and which, in the case of the AFL, reigns almost alone' (ref 7).

Extract from R.H. Tawney’s report in FO 371/30676.

By the 1950s, the boot was on the other foot when it came to covert action. MI6 was disconcerted to receive CIA intelligence which appeared to come from a high-level American agent in the TUC. In fact, the report came from Lovestone's international labour network, although whether this means the initial impression was entirely mistaken is perhaps an open question (ref 1, p.247).

In 1955, a US labour attaché in Britain, the former Lovestoneite Joseph Godson, took part in a meeting at which Labour Party luminary Hugh Gaitskell planned the expulsion of his rival Aneurin Bevan, an episode which sparked much debate among spook-watchers on the British left (ref 9, p.14). The controversy acquired some of its edge because of the theory, prevalent in some intelligence circes, that Gaitskell's sussessor as Labour leader, Harold Wilson, was a Soviet mole. Among those who subscribed to this idea was Lovestone's CIA patron, counterintelligence chief James Angleton, though not reportedly Lovestone himself (ref 1, p.347).

By the late 1950s, the CIA was using Lovestone's AFL-CIO networks as a back-channel to bypass the British and make contact with independence movements in Africa (ref 1, p.285). This was partly to ensure that the State Department's links with the colonial powers did not leave the field free for the Soviets.

Anti-communism was the one consistent thread in Lovestone's otherwise complex role in the Anglo-American intelligence relationship. The lesson perhaps is that it is easy to over-estimate the degree of control implied by the language of 'fronts', and that even covert politics is, above all, politics.

References

Ref 1: Ted Morgan, A Covert Life - Jay Lovestone: Communist, Anti-Communist and Spymaster, Random House, 1999,

Ref 2: Keith Jeffery, MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service 1909-1949, Bloomsbury, 2010.

Ref 3: Notes on the Communist Opposition Movement, 6 December 1937, UK National Archives KV2/580.

Ref 4: Thomas E. Mahl, Desperate Deception: British Covert Operations in the United States, 1939-44, Brassey's, 1999

Ref 5: Sydney Morrell, SO1 New York Organisation Plan, UK National Archives FO 898/103.

Ref 6: David Dubinsky and A.H. Raskin, David Dubinsky: A Life With Labor, Simon & Schuster, 1977

Ref 7: R.H. Tawney, Report by Professor Tawney on Sir W. Citrine's Visit to the United States, UK National Archives FO 371/30676.

Ref 8: Robert J. Alexander, The Right Opposition: The Lovestoneites and the International Communist Opposition of the 1930s, Greenwood Press, 1981.

Ref 9: Stephen Dorril and Robin Ramsay, Smear! Wilson and the Secret State, Fourth Estate Limited, 1991.