Senator Frank Church (public domain).

In February 1976, US Senator Frank Church was presiding over the final weeks of a momentous select committee inquiry into the CIA. British Prime Minister Harold Wilson was in the final months of his premiership, a period in which he was increasingly concerned about the machinations of right-wing intelligence officers against him.

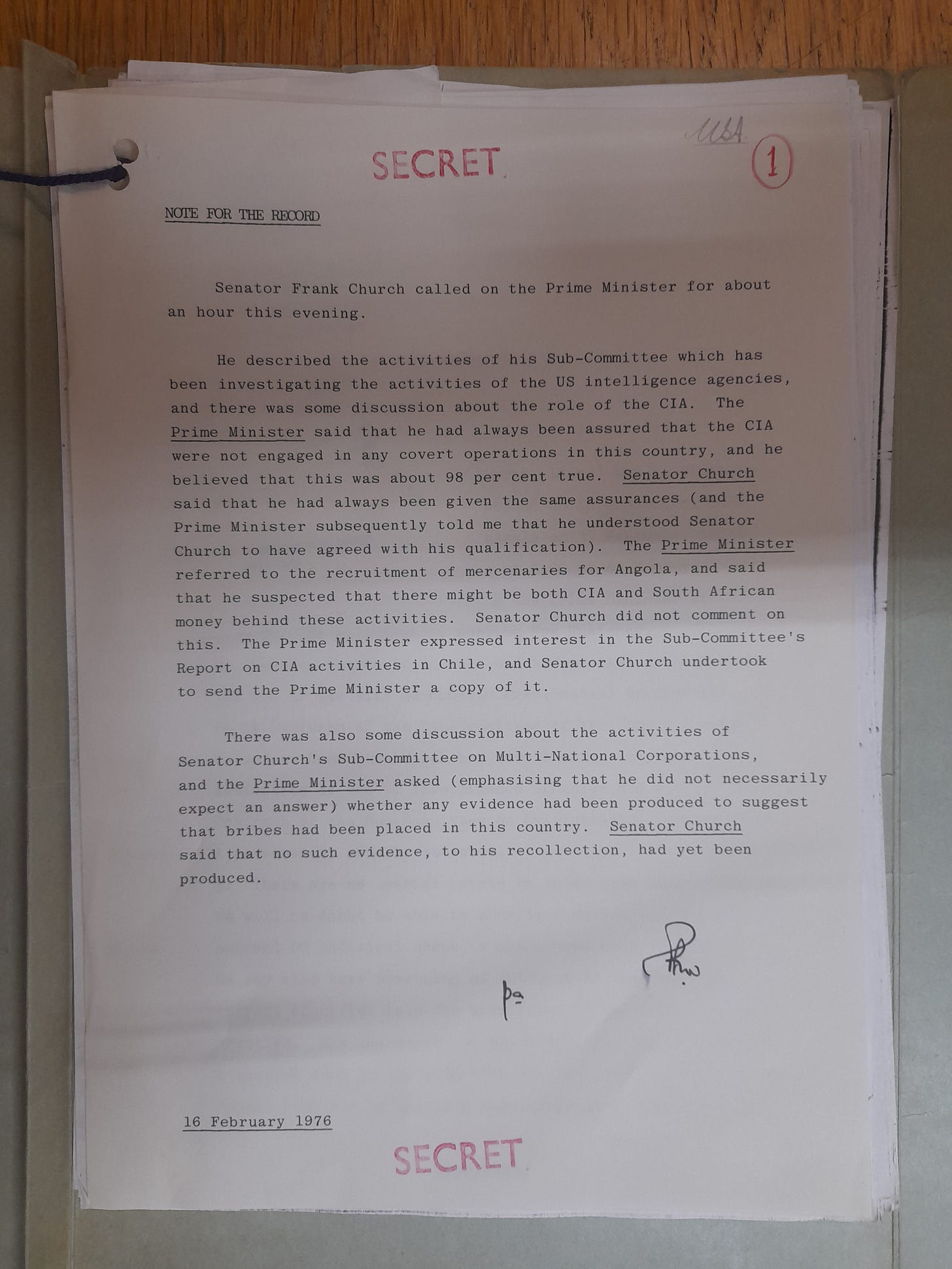

I was naturally intrigued to find the record of a meeting between the two men during my latest trawl for CIA-related material at the UK National Archives Most of the file turned out to be press cuttings about Senator Church. The crucial document is a single page, which I reproduce below.1

Frustrating as it is, the ambiguity about the ‘98 per cent’ figure is telling in itself of how Wilson’s perceptions on intelligence matters diverged from those of his officials.

His modest 2 per cent of doubt is arguably justified by developments in Anglo-American intelligence liaison over the preceding 15 years, during which both British and American officers fuelled the conspiracy theories of Soviet defector Anatoly Golitsyn about Wilson and many others.2

Wilson was definitely onto something about Angola. As he spoke a disintegrating band of mostly British mercenaries was retreating across the border towards Kinshasa. 14 men had been executed by their own leaders, and another, former CIA paramilitary officer George Bacon II, had been killed in a Cuban ambush.3

The CIA’s Angolan Task Force, codenamed IAFEATURE, was headed at the time by John Stockwell, who later wrote of the British mercenaries’ recruitment:

No memos were written about this operation at CIA headquarters and no cables went out approving it. Since it overlapped extensively with our other activities, however, we became increasingly concerned at headquarters. IAFEATURE airplanes were carrying these fighters into Angola. They were being armed with IAFEATURE weapons. Their leaders met with CIA officers at IAFEATURE safehouses in Kinshasa to discuss strategy and receive aerial photographs and briefings. It seemed likely [Holden] Roberto was using CIA funds to hire them.4

Stockwell described the quality of the recruits as ‘exceptionally low.’ At least one of the mercenaries who died in Angola was later implicated in the Bloody Sunday killings in Northern Ireland four years earlier.5

One interesting question is whether British intelligence had more definite information about the mercenaries than the Prime Minister did. One of their recruiters, Les Aspin, claimed to have links to MI6.6

Update: I have edited this piece to correct the first name of the Russian defector Golitsyn, which was Anatoly, not Oleg.

National Archives file PREM 16/1150. Apologies for the lighting of the image, which is a bit hit and miss at the archives’ camera desks!

For some previous research using this file see Dafydd Townley (2022) Too responsible to run for president: Frank Church and the 1976 presidential nomination, Journal of Intelligence History, 21:2, 213-231, DOI: 10.1080/16161262.2020.1826813.

The story is well-told in David Leigh, The Wilson Plot, Mandarin, 1989, and Stephen Dorril and Robin Ramsay, Smear! Wilson and the Secret State, Fourth Estate Limited, 1991.

Tony Geraghty, Guns for Hire: The Inside Story of Freelance Soldiering, Piatkus Books,2008, p.72.

John Stockwell, In Search of Enemies, Norton, 1978, pp.223-4.

Allison Morris, The soldier and the colonel: A key soldier involved in Bloody Sunday had a colourful post-Army career but his final resting place remains unknown, Belfast Telegraph, 8 May 2022.

Geraghty, p.65.