Welcome! I’m Tom Griffin and this is my intelligence history newsletter. Feel free to share this post with the button below.

Britain’s former colonies have provided one of the richer seams of intelligence-related material from the UK National Archives in recent years. In the 1950s and 60s, the Colonial Office’s network of security liaison officers (SLOs), run by MI5’s E Branch, was the closest MI5 came to realising its aspirations of being an imperial security service.

Back in November I wrote about the tensions between MI5 and the CIA in East Africa, as the Americans moved into Britain’s colonies in anticipation of independence. This week, I came across evidence of a more cordial side to the relationship between the two agencies.

It came in a collection of migrated archives from colonial governments, deposited in the archives at Kew a decade ago, but removed for three months in 2022 because of evidence they had historically been treated with insecticide.1 Researchers are now required to handle the documents with plastic gloves in a special reading room.

The two files I was after consisted of SLO reports from the Gambia, a country which is not mentioned in the most comprehensive account of the SLO network, Calder Walton’s Empire of Secrets. As it turns out, Gambia came under the aegis of the SLO based in Sierra Leone, whose post was abolished in 1965 according to Walton.2

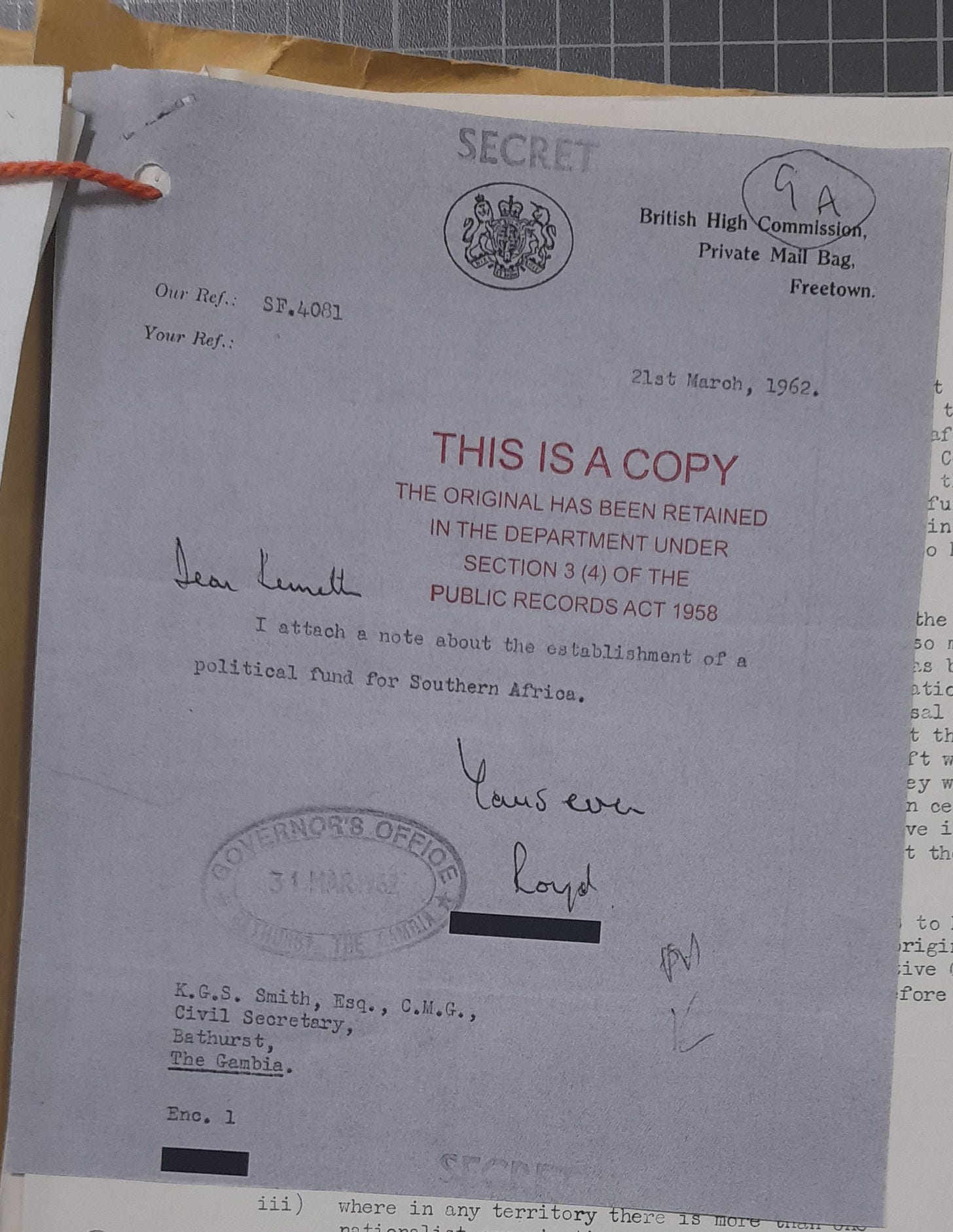

I was hoping to learn more about some of these SLOs, but their names were redacted, something which hasn’t always been the case in recent years. One clue may have slipped through, however.

In the letter above the SLO’s printed name has been blacked out but his hand-written signature remains.3 My guess is that this a glimpse at the early career of Royd Barker, who headed MI5’s A Branch in the 1980s.

Most of the Gambia files concern the circulation of documents about Soviet front organisations. There was particular concern about Eastern bloc offers to train African workers.

One potential response to this problem emerges from a proposal which the SLO in Freetown passed on to the Gambia in August 1961, outlining a scheme to train African civil servants in Lebanon.

…the primary need is for public administration training. This training must be effective; it must be given quickly on a “crash” basis; it must be given in such a way that those receiving it are not embarrassed by being made subject to a charge of having become “imperialist agents.”

Lebanon was put forward as an ideal site.

It is a comparatively near-at-hand neutral point outside of Africa; it is a small country without imperialist ambitions; its climate is suitable for Africans; its second language, French, is the second language of most of the trainees. The trainees would feel at home in Lebanon; they would enjoy their stay; and they would not be embarrassed by their association with this country.4

The suggestion must have had a certain plausibility given the existence of a significant Lebanese diaspora in West Africa. Yet the aspiration towards a neutral image was at odds with the identity of the scheme’s promoters, the Lebanese-American firm of Copeland, Eichelberger and Scott (CE&S).

Copeland & Eichelberger had been formed in 1957 by two former Middle East hands at the CIA, Miles Copeland and James Eichelberger.5 For the purposes of the scheme they proposed to link up with Don Scott Associates.6 The latter firm is more obscure but Copeland’s autobiography mentions a cousin named Don Scott.7

MI5’s interest in the scheme suggests an intelligence connection, but was it more than the old boy network looking favourably on a private initiative? Copeland & Eichelberger was a genuine firm, whose biggest business was liaising between Gulf Oil and the Kuwaiti royal family from its Beirut base. However, Copeland still carried out tasks for the CIA, monitoring the suspected Soviet mole Kim Philby for James Angleton and keeping up his connection with Zakaria Mohieddin, the founder of Egypt’s General Intelligence Service.8

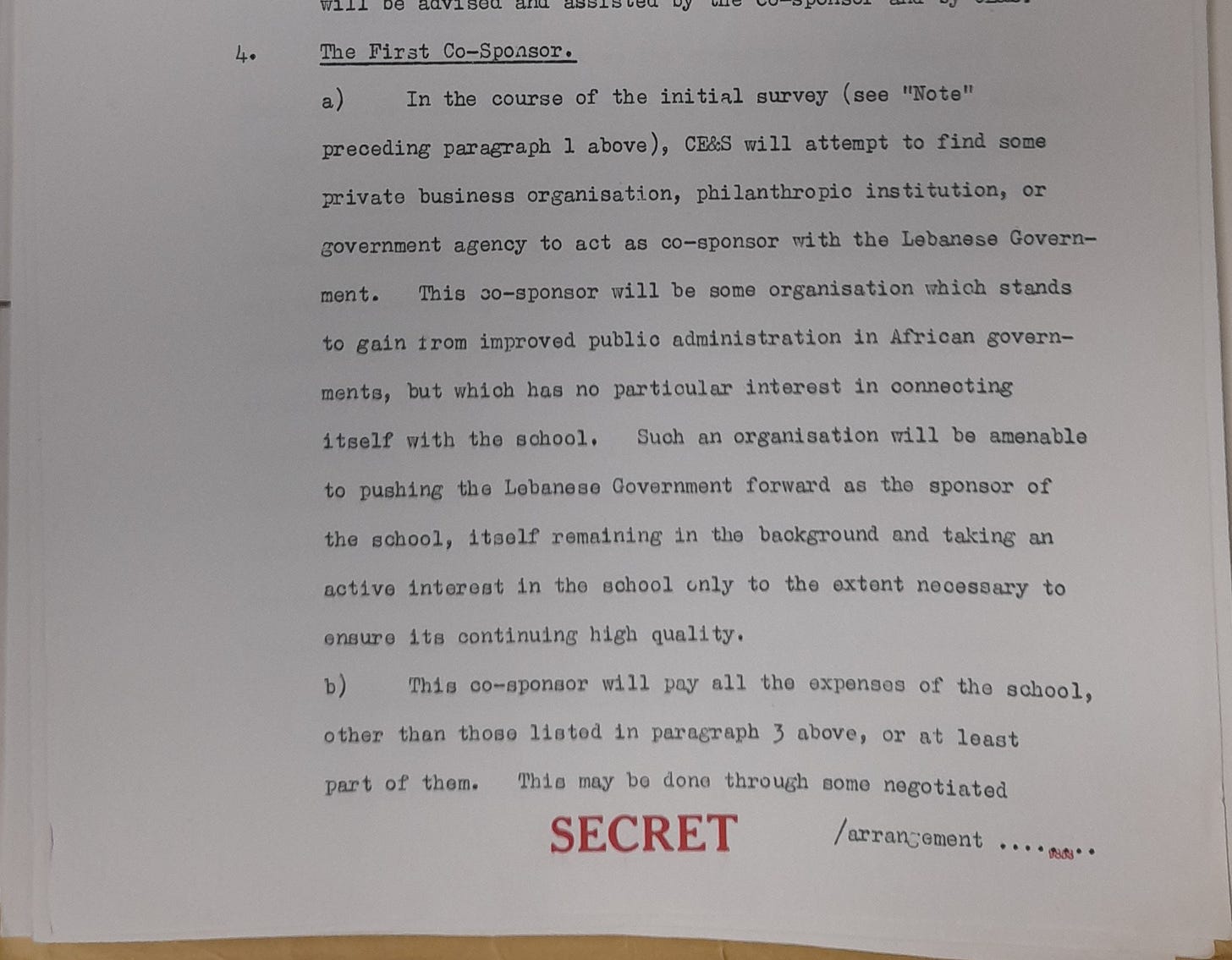

The section of the proposal on funding arrangements is suggestive.

The proposal suggests that prospective co-sponsors could include corporations, the Rockefeller or Ford Foundations, and the United Nations.9 Yet the patron content to remain in the background is surely a neat fit for the CIA.

That might mean the idea was inspired by the agency, like so many other transnational organisations of the Cold War. It might also mean it was an enterprise designed by Copeland with the CIA in mind.

The figure portrayed in Copeland’s admittedly self-mythologising autobiography does not come across as a natural school principal. Nevertheless as Hugh Wilford notes in his account of the CIA’s early Arabists, America’s Great Game, Copeland was a strong proponent of elite theory as propounded by James Burnham.10 Such ideas might well have inspired an initiative aimed at moulding future African leaders. Indeed, the scheme’s specific exclusion of ‘political philosophy’ and ‘free elections and democratic institutions’ from the school’s curriculum has something of the Burnhamite flavour of Copeland and Eichelberger’s previous approach as CIA officers in Egypt.11

It’s not clear if anything ever came of the proposal, but someone in Whitehall seems to have liked it.

What is FCO 141 and why did The National Archives remove it from public domain? Cambridge Centre Of African Studies Library Blog, 13 July 2023.

Calder Walton, Empire of Secrets: British Intelligence, the Cold War and the Twilight of Empire, William Collins, 2013, p.273.

National Archives FCO 141/4833. Note to K.G.S. Smith, 21 March 1962.

National Archives FCO 141/4832. Lebanon/U.A.R./Africa, Political Proposal for the training of African Civil Servants in Lebanon (May 1961). Part 1: Some Background Considerations, p.2.

Miles Copeland, The Game Player: Confessions of the CIA's original political operative, Aurum Press, 1989, p.211. Despite his high profile and significance in Middle Eastern history, Copeland is probably best known, in the English-speaking world at least, as the father of Stewart Copeland, the drummer in The Police.

There seems to be a board game company of that name, and there may be a connection given that Copeland himself designed a political strategy game, The Game of Nations. It is striking, though no doubt logical, how much the history of wargaming comes up in the history of intelligence.

Copeland, p.11.

Copeland, p.211-13.

National Archives FCO 141/4832. Lebanon/U.A.R./Africa, Political Proposal for the training of African Civil Servants in Lebanon (May 1961). Part II: The Proposal, p.4.

Hugh Wilford, America's Great Game: The CIA's Secret Arabists and the Shaping of the Modern Middle East, Basic Books, 2013, p.149.

National Archives FCO 141/4832. Lebanon/U.A.R./Africa, Political Proposal for the training of African Civil Servants in Lebanon (May 1961). Part 1: Some Background Considerations, p.4.