How Whitehall saw the Year of Intelligence

US investigations of the mid-1970s threatened to expose British covert funding of news agencies

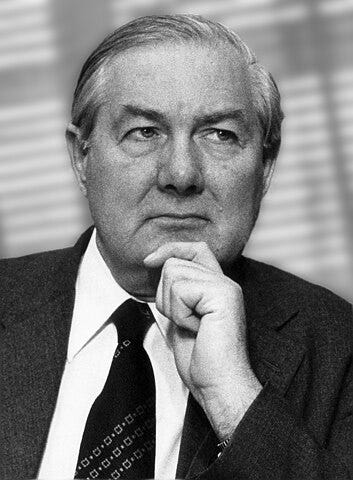

As Foreign Secretary, James Callaghan had to deal with the fallout from US Congressional investigations (European Communities, 1975, CC.4.0).

In December 1974, The New York Times broke the story of the CIA’s illegal spying in the United States, based on the agency’s own internal audit - ‘the Family Jewels.’1 The unprecedented wave of investigations that followed led to 1975 being dubbed ‘the year of intelligence.’2

Spycatcher, by MI5 officer Peter Wright, provides a vivid account of the impact of events in the US on the British intelligence community.

We were the modern pariahs - hated, distrusted, hunted.

Oldfield and Hanley were terrified by the pace of events abroad, fearful above all that some of the revelations would spill over onto their own services (ref 3, p.377).3

At Westminster, the revelations gave new life to claims that espionage operations against Britain where being run from the US Embassy, where covert action expert Cord Meyer was the CIA station chief.

In February 1975, the minister responsible for MI5 and thus counter-espionage, Home Secretary Roy Jenkins, told the Commons:

The report about CIA activities in this country was categorically denied by the American Embassy after it was published just over a year ago. I have no reason to think that that denial was not accurate. Certainly there would be no countenancing of any illegal activities by the agents of any Government in this country.’4

The British government’s own concern was much more about the exposure of CIA operations in which it was itself involved, something which became increasingly likely as the investigations developed.

A Washington Post story on 16 January 1976 linked a Reuters-managed press agency in Latin America to the CIA.5 The following day, the Post reported on Forum World Features, a CIA funded press agency based in London.6

Forum World Features had already been exposed by Time Out at this point, but Foreign Secretary James Callaghan was sufficiently concerned to cable the Washington embassy (ref 7).7

Ambassador Peter Ramsbotham raised the matter with Proctor of the CIA, possibly the Director of Intelligence, Edward Proctor, who pointed out the Post story referenced a ‘former agency official’ (ref 7).8

Ramsbotham told London that he suspected the recently retired head of the agency’s Western Hemisphere Division, ‘David Phillips, the Ex-CIA officer who has now established himself as the local fountain of wisdom of intelligence questions’ (ref 7).

Proctor denied that the CIA were using Reuters ‘for planted stories or any other kind of covert action,’ according to Ramsbotham, who reported that ‘the CIA continue to abide by their longstanding agreement with us that they would not recruit British nationals for clandestine purposes.’9

What this meant in practice was that using Reuters for covert action was a British prerogative. It was revealed in 1992 that the Foreign Office’s propaganda arm, the Information Research Department (IRD), had funded Reuters operations in the Middle East and Latin America under a 1969 agreement.10

The CIA’s public denial, at British behest, that it was manipulating Reuters presumably did not preclude collaboration with this British effort.

Such co-operation certainly took place in relation to Forum World Features, as is acknowledged in a Foreign office brief for Callaghan’s successor, Anthony Crosland, on CIA activities in the UK.

This recorded the official position that ‘we would initiate an enquiry into CIA activities in Britain only if evidence were produced of inadmissible or illegal activities.’11

We have been confident in sticking to this line because we are as sure as we can be that the CIA are not in fact engaged in any improper activities here. Indeed, it would be most damaging to the US-UK intelligence relationship if the CIA were ever found out indulging in activities here without our knowledge and consent. Our relationship is one of mutually valuable confidence and partnership. To put it in no higher terms, the potential damage to US interests were they to behave in this way and to be found out, is such that even were they to be tempted they would refrain. I doubt in fact if they have even felt mildly tempted.12

According to the brief by R.A. Sykes, most stories about the CIA in Britain ‘concerned spurious allegations about industrial espionage, penetration of British trade unions and political parties, recruitment of mercenaries and other such activities.’13

Sykes did acknowledge some exceptions.

On one or two occasions, the radical press in Britain has come fairly close in its references to certain jointly approved CIA activities, but these have not resulted in any specific Questions in Parliament. For example, Time Out has mentioned that the news feature service, Forum World Features, which was wound up in April last year, had CIA backing. This was true, but with then Secretary of State’s concurrence we had decided to ask the CIA to close the agency down before any story, possibly leaked by Mr Agee, broke.14

Parts of the brief are still redacted, and it offers no further examples of jointly approved activities, although these may have overlapped with the otherwise ‘spurious allegations’. The Information Research Department, whose responsibilities paralleled parts of the CIA’s Covert Action Staff, would have been a key player along with MI6.

Despite the fears of intelligence chiefs, British legislative scrutiny, reflected in occasional parliamentary questions, never approached the level of the American Congressional committees.

Nevertheless, there were parallels between the two countries, as Cold War covert operations were scaled down for an era of détente. Crosland set an early test for IRD by asking for a brief on South Africa. The test was failed when the department sent back a paper on the Communist threat in the country, ignoring the apartheid regime.15 His successor David Owen abolished IRD outright.16

The parallels would continue into the 1980s, as cold warriors on both sides of the Atlantic looked to a new wave of political leaders for their restoration.

The CIA's Family Jewels, National Security Archive, 21 June 2007.

Year of Intelligence, New York Times, 8 February 1975.

Peter Wright, Spycatcher: The Candid Autobiography of a Senior Intelligence Officer, Viking, 1987, p.377.

House of Commons Hansard, Oral Answers To Questions, Thursday 6 February 1975.

Walter Pincus, CIA Funding Journalistic Networks Abroad, Washington Post, 16 January 1976.

Walter Pincus, Panel monitors CIA news ‘plants’, Washington Post, 16 January 1976.

UK National Archives, FCO 82/671, Activities of US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), 1976 Jan 01 - 1976 Dec 31.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Guy Faulconbridge, Britain secretly funded Reuters in 1960s and 1970s - documents, Reuters, 13 January 2020.

UK National Archives, FCO 82/671, Activities of US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), 1976 Jan 01 - 1976 Dec 31.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Paul Lashmar and James Oliver, Britain's Secret Propaganda War 1948-1977, Sutton Publishing, 1998, pp.167-68.

Ibid, p.168.