The CIA and European Unity

How covert American support sustained the European Movement

Welcome! I’m Tom Griffin and this is my intelligence history newsletter. Feel free to share this article with the button below.

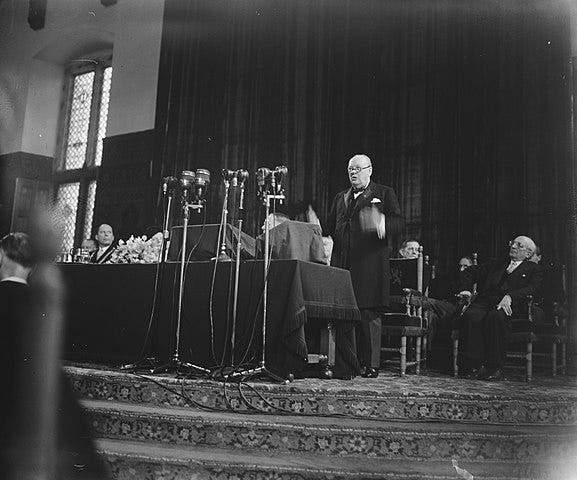

Churchill addressing the Congress of Europe in 1948, shortly before the CIA stepped in to bail out the organisers (Nationaal Archief - Dutch National Archives, CC1.0).

Lenin apparently never quite said that ‘here are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen’, but last week was one of those weeks for transatlantic relations.

On Wednesday, Donald Trump told his inaugural cabinet that ‘the European Union was formed in order to screw the United States.’ At any other time that would have been a major diplomatic shock in its own right.

Among the European leaders who responded was Polish president Donald Tusk, who tweeted that the EU ‘was formed to maintain peace, to build respect among our nations, to create free and fair trade, and to strengthen our transatlantic friendship.’

The historical record shows that it was Europe’s most pro-American politicians who pioneered the cause of continental unity, and that in the early years they relied on the help of the CIA to do so.

In the late 1940s, European federalism complemented the Marshall Plan goal of modernizing the continent’s economy to stave off communist influence. It also offered a context in which German re-armament could take place without re-igniting national rivalries.

In 1948 influential politicians from across the continent gathered at the Hague for a Congress of Europe, demonstrating the potential of the cause. Unfortunately, the effort almost bankrupted the organisers, the incipient European Movement.

Help soon materialised in the form of the American Committee for a United Europe (ACUE), headed by former OSS chief William Donovan as chair, with the OSS’s wartime representative in Switzerland, Allen Dulles, as vice-chair, and a third OSS veteran, Thomas Braden, as executive director.1

This was fairly light cover for a CIA operation which provided the European Movement with some $4 million between 1949 and 1960, the period which witnessed the creation of the European Economic Community.2

While the role of the CIA in sustaining the European Movement is no longer in doubt, what’s more open to question is how far this support for a private campaigning organisation shaped the inter-governmental drive towards unity. Ironically, historian Richard Aldrich suggests that ACUE over-estimated the impact of public opinion on the foreign policies of European governments.3

Yet Aldrich also shows that the initiative in soliciting ACUE funds often came from the Europeans, typically figures with intelligence links of their own.

The origins of the programme, lay less in the formal provisions of National Security Council directives, which CIA historians have studied ad nauseam, and more in an informal and personal transatlantic network. This was a pattern of human friendships created by members of the intelligence and resistance community during the Second World War.4

The founding Secretary-General of the European Movement was Józef Retinger, a former adviser to the Polish Government in Exile, who had been parachuted into his home country by the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) in 1943. The first president was former War Office Minister, Duncan Sandys.5 Among the honorary presidents was the man who had ordered SOE to ‘set Europe ablaze’, Sandy’s father-in-law Winston Churchill.6

As in many of its other operations of the late 1940s, the CIA was effectively supporting the re-orientation of Second World War networks to the new circumstances of the Cold War. The movement for European unity was partly a movement against the new division of Europe by the Iron Curtain.

The CIA’s role was a classic case of covert action as a matter of finding and aiding allies, rather than creating them ex nihilo. British involvement demonstrated the limitations of what the Americans could achieve.

As enthusiasm for a federalist approach to unity grew on the continent, Sandys and Churchill got cold feet. The Labour Government was even more hostile, regarding federalism as a distraction from the US alliance, in spite of the Americans’ own view. The party leadership isolated the most outspoken federalist in its parliamentary ranks, the ACUE and hence CIA funded R.W.G. Mackay.7 The limits of American influence were illustrated most starkly in 1962 when the staunchly Atlanticist Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell set his face decisively against entry into the Common Market.8

It was a Conservative Government that took Britain into the European Economic Community - for a generation - in 1973. While one can debate the impact of the CIA’s involvement, the agency’s early Cold War aims were ultimately well-served as European unity came to embrace East as well as West.

Donald Trump’s elision of this history could be put down to lack of knowledge, but it may also reflect the logic of an America First position which is basically hostile to the political consequences of the Second World War - and to those human connections forged in the fires of the resistance.

Richard J. Aldrich, The Hidden Hand: Britain, America and Cold War Secret Intelligence, Overlook Press, 2002, p.347.

Aldrich, 2002, p.343.

Aldrich, 2002, p.368.

Aldrich, 2002, p.344.

Hugh Wilford, The CIA, the British Left and the Cold War: Calling the Tune? Frank Cass, 2003, p.228.

Aldrich, 2002, p.343.

Wilford, 2003, p.237.

Wilford, 2003, p.225.

A good book probably out of print is “The CIA and the Marshall Plan” by Sally Pisani.