Welcome! I’m Tom Griffin and this is my intelligence history newsletter. Feel free to share this post with the button below.

As in many countries with a British colonial past, imperial and Commonwealth connections played an important role in the early history of Pakistan’s intelligence services. However, some widely available accounts of those links are particularly confused in the case of Pakistan’s best-known intelligence agency, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI).

Pakistan’s earliest agency was the civilian Intelligence Bureau (IB), which like its Indian namesake drew on the heritage of the colonial-era Delhi Intelligence Bureau (DIB).

In intelligence, as in other areas, India inherited the bulk of the assets. However, the second-in-command of the DIB, Ghulam Ahmed, took a number of files with him when he joined the cross-border exchange of populations at independence, and founded the Pakistani IB.1

Pakistan was keen to maintain British intelligence liaison. According to Calder Walton, it was on the initiative of Pakistan, not Britain, that MI5 appointed a Security Liaison Officer in Karachi in 1951, matching the one already in place in Delhi.2

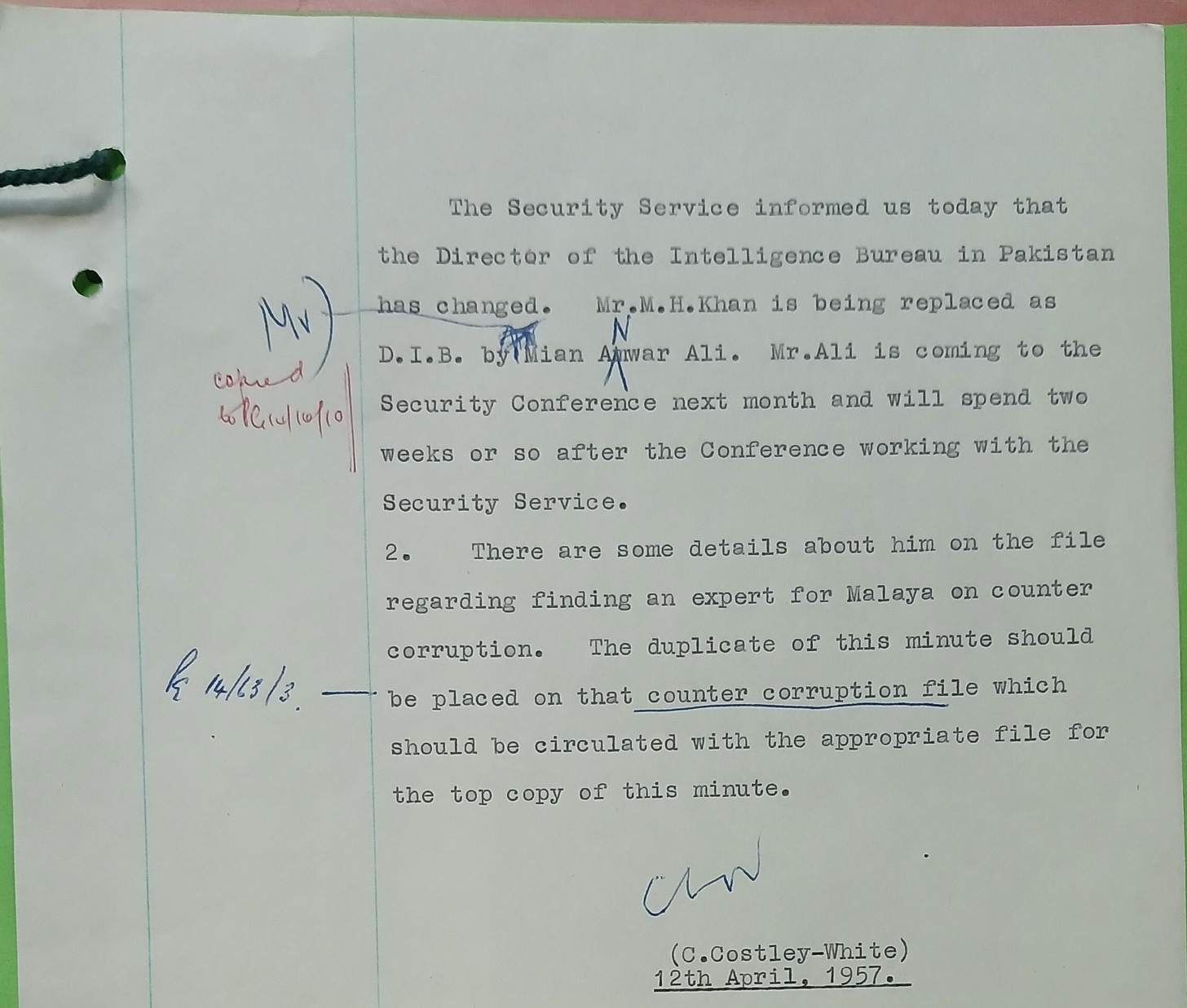

The relationship evidently prospered as by 1957, the SLO was describing the incoming IB director, Mian Anwar Ali, as ‘very friendly and pro-British in outlook.’3 Indeed, Ali seems to have spent some time working in London with MI5 at this point.4

No doubt it helped that India had begun to tilt towards Moscow by this time, although the Indian IB still maintained close relations with MI5.5

The British relationship was also central to defence intelligence. When the ISI was founded in around 1948, one of its main components was a Joint Intelligence Bureau (JIB) modelled on the one established in Britain by Kenneth Strong in 1946, and intended to plug into a network of similar Commonwealth organisations within which Pakistan and India were theoretically partners.6

The ISI’s fateful assumption of an internal counterintelligence role may also have been intended to provide security assurances that would promote British confidence.7

One factor which bolstered the relationship was the continuing presence of British officers in the Pakistani Army for several years after independence. At least one former British Army officer played a formative role in the ISI, although accounts of this appear contradictory.

The English language Pakistani paper The News published a list of ISI chiefs in 2018, reporting that ‘Australian-born Major General, Robert “Bill” Cawthome, remains the longest-serving Director General of the Inter-Services Intelligence Agency for over nine years from 1950 to 1959.’8

However, a monograph on the ISI by former DIA officer Owen Sirrs gives a very different account of the same period, which followed the departure of the ISI’s founding director Syed Shahid Hamid in 1950.

Hamid’s immediate successor appears to have been Brigadier Mirza Hamid Hussain. But Hussain’s tenure was a short one, and within a year he was transferred to the Pakistani Foreign Service. Other directors in this time period include Syed Ghawas, Malik Sher Bahadur and Mohamed Hayat Khan.9

At the time of writing, the Wikipedia page on ISI directors reproduces the confusion, repeating the claim about Cawthome immediately before a list which does not include him, but does mention the names cited by Sirrs.10

Sirrs’ account cites copious sources, including files from the UK national archives and autobiographies of ISI officers. It is surely the correct one. Yet the alternative version continues to circulate because it is widely available on the internet.

Reference in the News article to ‘Robert Cawthome’ having been Deputy Chief of Staff in the Pakistan Army suggests that the confusion may have originated in a garbled reference to Walter Cawthorn, who held that position from 1948 until 1951, after serving as a senior military intelligence officer in British-ruled India during the Second World War.11

According to Sirrs, Cawthorn did indeed play a leading in ISI’s creation, along with Syed Shahid Hamid.12 Yet for much of the period when he is supposed to have been ISI chief, he was actually leading another Commonwealth intelligence organisation.

From 1952 to 1954, he directed Australia’s Joint Intelligence Bureau, before returning to Pakistan as Australian High Commissioner until 1959.13 He ended his career in the 1960s as Director-General of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service, an antipodean equivalent to MI6.14

It’s perhaps appropriate that such a varied intelligence career has become wrapped in a cloak of confusion.

Owen L. Sirrs, Pakistan’s Inter- Services Intelligence Directorate: Covert action and internal operations, Routledge, 2017, p.17.

Calder Walton, Empire of Secrets: British Intelligence, The Cold War and the Twilight of Empire, William Collins, 2014, p.138.

D.J. Scherr, Box 500, to C.G. Costley-White, Commonwealth Relations Office, 2 May 1957. UK National Archives DO 231/50.

C.G. Costley-White, Commonwealth Relations Office, 12 April 1957. UK National Archives DO 231/50.

Calder Walton, Empire of Secrets: British Intelligence, The Cold War and the Twilight of Empire, William Collins, 2014, p.137.

Owen L. Sirrs, Pakistan’s Inter- Services Intelligence Directorate: Covert action and internal operations, Routledge, 2017, p.19.

Owen L. Sirrs, Pakistan’s Inter- Services Intelligence Directorate: Covert action and internal operations, Routledge, 2017, p.20.

Sabir Shah, Average tenure of 22 ISI chiefs in 70 years has been 3.18 years, The News, 12 October 2018.

Owen L. Sirrs, Pakistan’s Inter- Services Intelligence Directorate: Covert action and internal operations, Routledge, 2017, p.34.

Director-General of Inter-Services Intelligence, Wikipedia, accessed 31 August 2024.

Lord Casey, Major-General Cawthorn dies, The Age, 7 December 1970.

Owen L. Sirrs, Pakistan’s Inter- Services Intelligence Directorate: Covert action and internal operations, Routledge, 2017, p.18.

Lord Casey, Major-General Cawthorn dies, The Age, 7 December 1970.

Owen L. Sirrs, Pakistan’s Inter- Services Intelligence Directorate: Covert action and internal operations, Routledge, 2017, p.33.

Mian Anwar's predecessor M.H. Khan was Bengali by ethnicity and suffered the same fate as those of his ethnic political elites of the time: dejection, unwarranted discrimination and a collective banishment from national memory in Pakistan largely by the British-patronised Generals. Based on his reported engagement with CIA's Allen Dulles, he was 'not dove-ish' toward his Western contemporaries.

I was able to profile him, which remains the only public record of his service in IB. Again, regrettably, archives in Pakistan have chosen not to discuss him.

https://open.substack.com/pub/intelligencenuggets/p/muazzam-husain-khan