The Third Coming of the Information Research Department

The Cold War propaganda model that exercises a perennial fascination for British think-tanks

Welcome! I’m Tom Griffin and this is my intelligence history newsletter. Feel free to share this article with the button below.

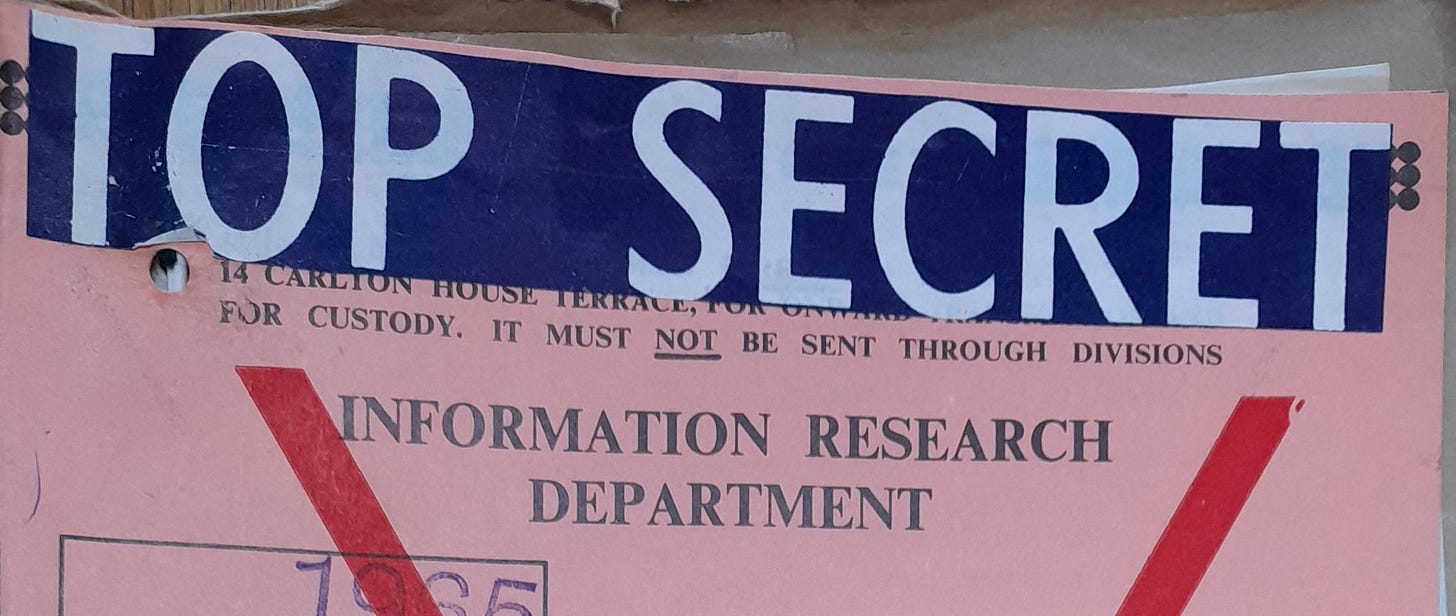

An IRD file released in 2019 (UK National Archives).

The opening of the archives of the Foreign Office Information Research Department (IRD) has been a key development for British intelligence historians in recent years. Although not strictly an intelligence agency, the IRD played a key role in British covert action during the Cold War until its abolition in 1977.

File releases have shed light on events from Indonesia to Italy. The IRD’s main activity was providing off-the-record briefings to journalists and other opinion formers. Yet this hid another, more secret role, producing targeted disinformation.

Among the operations revealed was an attempt to undermine the Black Power movement in the late 1960s, through a fake West African pamphlet attacking civil rights activist Stokely Carmichael as an American interloper.

Despite the many controversies attached to its record, some still see the IRD as a model. A new British think tank, the Council on Geostrategy, recently posted a roundtable article on the question: Does the Foreign Office need a new Information Research Department?

Among the seven experts consulted, the argument was finely balanced, although the idea was also supported in a follow-up article by Rory Cormac, the intelligence scholar who uncovered the Carmichael story.

There is a certain ambiguity in the debate, about what exactly it is intended should be revived: counter-narrative research and planning, unattributable briefing, disinformation, or all three?

It is, in any case, unclear how far these capabilities disappeared when IRD did. Its work always overlapped with MI6’s Special Political Action (SPA) section.1 This was itself reportedly abolished in another piece of mid-1970s intelligence retrenchment, but an equivalent was recreated in the 1990s under the name Information Operations (I/Ops).2

According to Paul Lashmar and James Oliver, IRD was broken up in part because Labour Foreign Secretary David was concerned by its unclear lines of accountability between the Foreign Office and MI6, to which the department’s covert element was hived off. A rump research element remained in the Foreign Office as the Overseas Information Department.3 This seems to have survived indefinitely after becoming the Information Department in 1980.4

There remains a suspicion that, despite its origins under the Attlee Government, IRD had become partisan in the eyes of Labour ministers. One of the department’s founders, Lord Mayhew reflected: ‘I think that it probably expanded its sphere of operations too far. I mean, there is a limit to what you ought to do with taxpayers’ money and I think perhaps some governments were tempted to use IRD for their political purposes. I don’t know. I’m only guessing.’5

As Rory Cormac’s article notes, calls to revive the IRD have come before. At the height of the War on Terror in 2006, the director of the Policy Exchange think tank, the current Lord Godson, wrote:

During the Cold War, organisations such as the Information Research Department of the Foreign Office would assert the superiority of the West over its totalitarian rivals. And magazines such as Encounter did hand-to-hand combat with Soviet fellow travellers. For any kind of truly moderate Islam to flourish, we need first to recapture our own self-confidence.6

The British Government was clearly listening. The following year, the Home Office established the Research, Information and Communications Unit (RICU) based on the IRD model and led by former MI6 officer Charles Farr. It works to disseminate counter-radicalisation messages through ‘discreet campaigns supported by Ricu without any acknowledgment of UK government support.’7

Journalist Peter Oborne has described this as ‘a con trick on the UK’s Muslim population.’

One Home Office official privately justified this to a journalist colleague of mine that ‘all we’re trying to do is to stop people becoming suicide bombers.’ But when the curtain was occasionally pulled aside a little thanks to investigative journalism, and the deception slowly became clear, the relationship between government and Muslim citizens became even more strained.8

Increased distrust is not infrequently the result of covert political action. For authoritarian states that may be an acceptable, even welcome, consequence. For democracies, it is more corrosive.

In his recent history of the CIA, Hugh Wilford has argued that the rise of modern conspiracy theory was itself in part an ‘unintended domestic consequence of the Agency’s overseas operations.’9

The War on Terror-era revival of interest in Cold War methods arguably had the same boomerang effect, particularly with the unravelling of the intelligence case for the Iraq War, which fuelled a huge wave of cynicism about editorial gatekeepers just a few years before the social media hordes were gathering to rush those gates. Such gatekeepers are fewer today and a new IRD would presumably, like RICU, be oriented towards social media - a swarm of individuals dominated by a few queen bees using algorithms instead of pheromones.

It will be harder to practise disinformation through the insertion of carefully crafted lie into a trusted system. The IRD and the CIA Covert Action Staff were in many ways the shadow of that system. the capacity to lie was founded on an acquaintance with the truth.

IRD staff included some eminent scholars and it was not unusual for MI6 officers to write learned papers on local archaeology or art history while on her majesty’s service. In the US, first the OSS and then the CIA drew in academic support on an industrial scale, encouraging the development of whole fields such as area studies.

The Council on Geostrategy scholars are most convincing when they allude to the threats facing independent journalism and swathes of the humanities, which underpin intelligence collection and analysis as well as the more esoteric art of covert action. The urgent question today is less whether these capabilities are enough than whether they can be sustained at all.

Note: This post was edited on 7 January to correct the name of the Council on Geostrategy.

Stephen Dorril, MI6: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service, Touchstone, 2000, p.787.

Philip H.J. Davies, MI6 and the Machinery of Spying, Frank Cass, 2004, p.297.

Paul Lashmar and James Oliver, Britain’s Secret Propaganda War 1948-1977, Sutton Publishing, 1998, p.171.

Foreign Office and Foreign and Commonwealth Office: Information Research Department: Registered Files (IR and PR series) and Publications Produced by Successor Bodies, Catalogue, UK National Archives, accessed 6 January 2025.

Paul Lashmar and James Oliver, Britain’s Secret Propaganda War 1948-1977, Sutton Publishing, 1998, p.171.

Dean Godson, The feeble helping the unspeakable, The Times, 5 April 2006.

Ian Cobain, Alice Ross, Rob Evans and Mona Mahmood, Inside Ricu, the shadowy propaganda unit inspired by the cold war, Guardian, 2 May 2016.

Peter Oborne, The Fate of Abraham: Why the West is Wrong about Islam, Simon and Schuster, 2022, p.262.

Hugh Wilford, The CIA: An Imperial History, Basic Books, 2024, chapter 6.