The CIA and MI5 in the British West Indies

How US pressured Whitehall over regional influence of Guyana's Cheddi Jagan

Cheddi Jagan and John F. Kennedy in 1961 (public domain).

Foreign relations are often used as a justification for redacting official files, but it can still be useful to take the indirect approach of using the archives of one country to shed light on another.

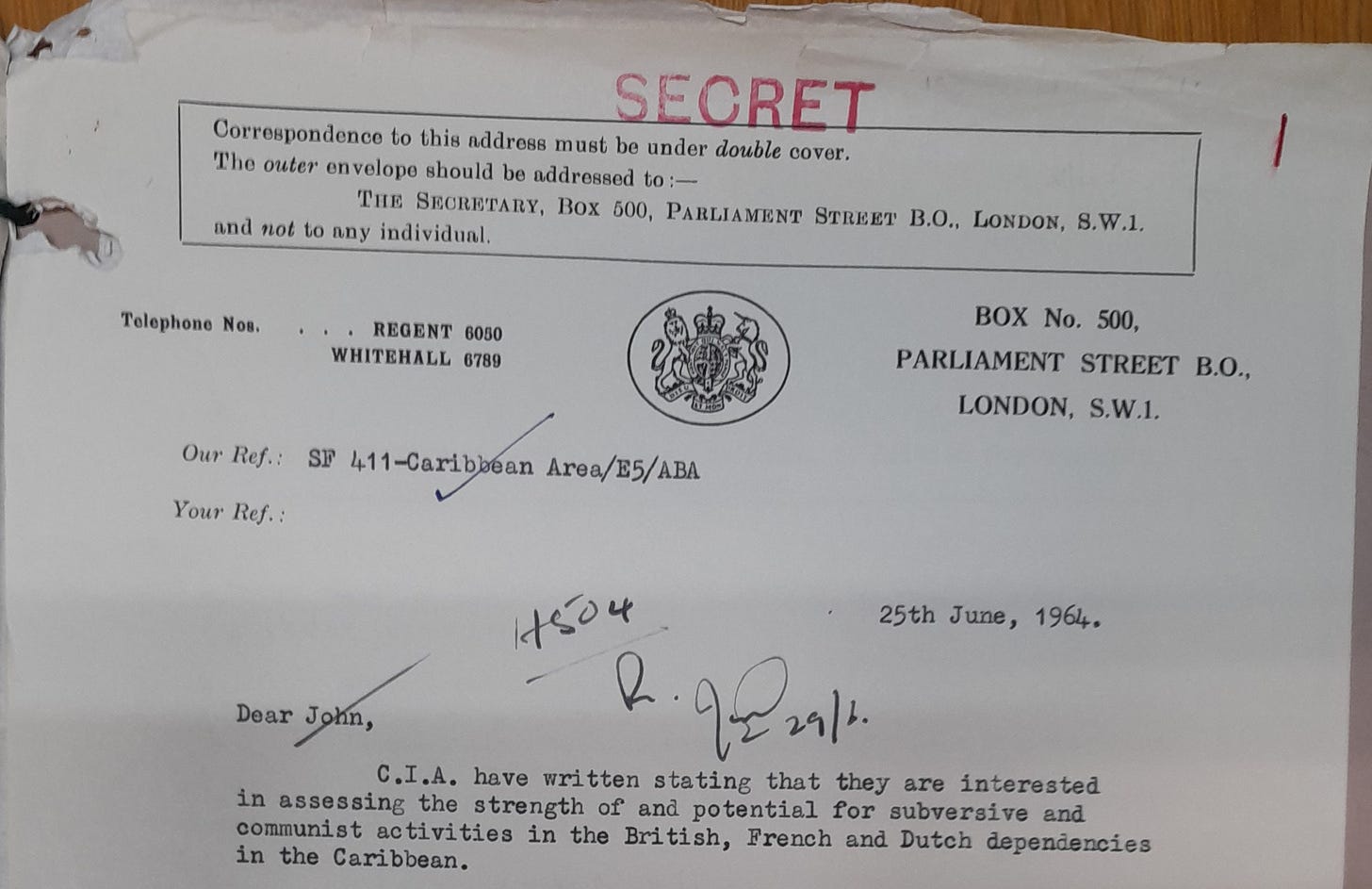

In September, I wrote about one British file which dealt with allegations of CIA covert action during the mid-1970s. On my most recent visit to the National Archives last week, I picked up CO1035/236, a Colonial Office file from 1964-65 on ‘United States intelligence activities in the Caribbean area’.1

This turned out to concern a CIA questionnaire sent to MI5 about subversion in Britain’s Caribbean possessions. Similar queries were apparently also made to the French and Dutch about their dependencies in the region.2

A. B. Arnott of MI5 passed the request to the Colonial Office, who concluded that ‘it would be better to supply them with our own considered assessment than to leave them to seek the information for themselves.’3

This was a delicate moment in the Anglo-American intelligence relationship. A string of security breaches, notably the defection of former MI6 officer Kim Philby in 1963, led the US to launch its own secret inspection of MI5 in 1965.4

In the Caribbean, the key element in the backdrop was the looming independence of British Guiana (soon to be Guyana), where American pressure had secured British agreement to a joint covert action against left-wing Prime Minister Cheddi Jagan.5

According to Christopher Andrew's official history of MI5, officers in the service’s Colonial division, E Branch were wary of covert action against a Commonweealth Government, and the MI5 role was confined to intelligence gathering, particularly through the Security Liaison Officer (SLO) in neighbouring Trinidad, who also had to liaise with Jagan’s wife Janet in her capacity as the Guyanese home affairs minister.6

Andrew records that ‘E5 minuted on the eve of independence that the Service was not being kept fully informed.’7 It is possible that E5 was Arnott, given the reference number on his letter.8

British Guiana itself was excluded from the questionaire, perhaps because the CIA was already in the lead. However, the first question referenced Jagan, asking ‘How susceptible are local conditions to Communist/Castro/Jagan/other subversive exploitation?’9

The tenth question asked ‘what evidence is there by attempts by Jagan or his Peoples Progressive Party to spread its influence in the Caribbean?’10

The responses from colonial governors argued that British Guiana was preoccupied with its internal problems, a line which downplayed the subversive threat without challenging the CIA’s assessment of Jagan. They nevertheless dutifully reported the presence of emissaries organising for the Caribbean and Guyana Conference of Youth for Freedom and Democracy.11

The consistency of the replies underlines that they were drafted in close consultation with the two MI5 officers in the region, the SLOs in Jamaica and Trinidad.12 Jamaica itself was not included in the responses to the questionnaire, perhaps because it had become independent in 1962, at which point the local government were informed of the presence of the-then SLO David Eastwood and of a newly-appointed CIA officer.13

The SLO in Washington DC provided a response on Bermuda which was ultimately not passed on because the island was not in the Caribbean. His response was nevertheless typical in finding the communist threat limited to two named individuals, one of whom was a past CPGB member resident in Britain ‘who may possibly return to the colony.’ He concluded that the greater security threat was actually 100 to 200 members of the Nation of Islam.14

The governor of Bermuda and the administrator of the Cayman Islands both stressed that economic links with the US were a bulwark against subversion. The latter noted that the only local labour organisation was the Global Seaman’s Union.15

..the office bearers in Grand Cayman are ‘clear’ to the extent that they are more influenced by the interests of National Bulk Carriers than by the interests of the union members. This state of affairs is recognised by a few ‘sea lawyers’ who, while resenting it, have so far done nothing about it.16

Elsewhere, trade union affiliations were the aspect of Caribbean politics most amenable to a Cold War interpretation, although in Dominica the main rival to the American-aligned ORIT federation was the Christian Democrat CLASC.17

The Chief Minister of St Vincent, Ebenezer Joshua, was reported to have received assistance from the Moscow-aligned World Federation of Trade Unions. This would no doubt have been a red flag for the CIA, although the British emphasised that ‘he is a careful to maintain a foot in both camps’ and that ‘taking his many shortcomings into account, he can scarcely be considered a really serious security risk.’18

Redactions in the files from St Vincent, Barbados, Grenada, and St Lucia suggest that subversion was regarded more seriously in the Eastern Caribbean, where economies were weaker.

The response from the small island of Monserrat noted that premier William Bramble ‘has said, in his wilder moments, that he would welcome Russian economic assistance. He is certainly not a communist or fellow traveller, but he is perfectly capable of flirting with communists, if only to try and provoke U.S. economic assistance.’19

Such tactics were perhaps not wholly at odds with the approach of the response itself. Drafted by the SLO Trinidad and the Monserrat administrator, it argued that ‘a solid economy is the Island’s best defence against subversion and it is through economic assistance that the U.S. Government could help most effectively to prevent it.’20

Grenada was felt to provide ‘a more promising field for left-wing subversion than any other British dependency in the Eastern Caribbean’, on the grounds that ‘it is a small, poor island with no industry and very few jobs to offer the growing educated element in its fast increasing population.’21

With the benefit of hindsight, of course, we know that a chaotic communist coup was only 15 years away, an event that would prompt the US invasion of 1983. Despite her ideological alignment with Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher was privately humiliated by the lack of consultation over the US deployment.22

The invasion underlined a shift in the balance of power between the two allies that was already apparent in the files from two decades earlier. CO1035/236 has something of the atmosphere of a Grahame Greene novel, in the spectacle of British spooks and civil servants doing their homework to answer the blunt questions of the CIA.

The resentments of the period have perhaps found their reflection in the stark accounts of the CIA’s role in Guyana produced by British intelligence historians.

CO1035/236 'United States intelligence activities in the Caribbean area', 1964 Jan 01 - 1965 Dec 31. UK National Archives.

Information requested by C.I.A. relating to British Dependencies in the Caribbean, 29 June 1964, National Archives, CO1035/236.

Secretary of State for the Colonies, 7 October 1964, CO1035/236.

Harold Jackson, Cleveland Cram obituary, The Guardian, 20 January 1999.

Christopher Andrew, Defence of the Realm, The Authorized History of MI5, Allen Lane, 2009, p.478. See also the accounts in Rory Cormac, Disrupt and Deny: Spies, Special Forces and the Secret Pursuit of British Foreign Policy, Oxford, 2018, pp.147-9; Calder Walton, Empire of Secrets: British Intelligence, the Cold War and the Twilight of Empire, William Collins, 2013, pp.159-162.

Walton describes the corrupt rule of Jagan’s US-backed successor Forbes Burnham as ‘a perfect illustration of the theory of ‘blowback’’. Jagan himself later returned to power and enjoyed cordial relations with the Clinton administration, albeit in a very different global context.

Christopher Andrew, Defence of the Realm, The Authorized History of MI5, Allen Lane, 2009, pp.478-479.

Christopher Andrew, Defence of the Realm, The Authorized History of MI5, Allen Lane, 2009, p.479.

Stephen Dorril reports that an Andrew Arnott was SLO in Cyprus in the early 1980s. Stephen Dorril, The Silent Conspiracy: Inside the Intelligence Services in the 1990s, Mandarin, 1994

Information requested by C.I.A. relating to British Dependencies in the Caribbean, 29 June 1964, National Archives, CO1035/236.

Information requested by C.I.A. relating to British Dependencies in the Caribbean, 29 June 1964, National Archives, CO1035/236.

CO1035/236 'United States intelligence activities in the Caribbean area', 1964 Jan 01 - 1965 Dec 31. UK National Archives.

Secretary of State for the Colonies, 7 October 1964, CO1035/236.

Governor of Jamaica, 30 April 1962, National Archives FCO141/5316.

A.B. Arnott to E.G. Donohoe, 25 November 1964, CO1035/236.

Information requested by C.I.A. relating to British dependencies in the Caribbean (Answers provided by the Adminstrator, Cayman Islands), CO1035/236.

Ibid.

‘Grenada’, December 1964, CO1035/236.

‘St Vincent’, February 1965, CO1035/236.

‘Monserrat’, 24 May 1965, CO1035/236.

Ibid.

‘Grenada’, December 1964, CO1035/236.

Robert Booth, National archives: Reagan blindsided Thatcher over 1983 Grenada invasion, The Guardian, 1 August 2013.